This article was first published in LooseLeaf Magazine and written during the summer of 2020.

Earlier this June, during the 2020 resurgence of Black Lives Matter, a controversy erupted in North American Asian artist and activism circles. An Asian artist had created an illustration depicting a yellow tiger and a black panther, set in a black and yellow yin yang symbol, with the slogan “Yellow Peril Supports Black Power” and hashtags “BlacksLivesMatter, #Asians4BlackLives” underneath. The image went viral online, as many Asian Instagram users re-posted it so that they too could show solidarity with the movement. However, as the illustration spread far and wide, criticism rolled in. Why were Asians centred in a Black Lives Matter illustration? Why had they dredged up the outdated ideas of “Yellow Peril” and “Black Power”? Why were they amassing social media clout on the back of Black lives?

In response, the artist took down the original illustration, but replaced it shortly after with an edited illustration. In it, the words “Yellow Peril Supports Black Power” were changed to “Black Lives Matter: We stand in solidarity.” Accompanying the updated art was a short apology about anti-Blackness in Asian communities and their mistake in centering Asians. Yet the image, which still visually centers Asians, lives on in the artist’s Instagram page, and as the profile picture on many fashionable Asian accounts. A month later, the artist started selling T-shirts featuring the illustration, with part of the proceeds going to Black organizations.

The widespread popularity and persistence of this controversial image speaks to where the Asian diaspora community in North America is today. We are all learning what it means to stand in solidarity with other people and movements, particularly with those with less access to power and resources. It is also an illuminating marker for where Asian artists are in our political journey as allies and accomplices. Unfortunately, the moral of this tale is that even when push comes to shove, many of us don’t know how to cede our place to others. But it doesn’t have to be this way.

In the rest of this essay, I will be highlighting examples from my work and that of others of how we can stand with and fight for others. I hope these stories will help further the conversation within our communities about how to be an effective artist-ally. This commitment to learning and growing is why I am not naming the artists and groups involved in the story above. We are all at different points in our respective journeys, and I respect that they are learning at their own pace. In addition, publicly shaming individuals rarely leads to a constructive end, and, in this case, will not address the tens of thousands of fans who liked and shared the image online.

1. Amplify other people’s art

Screenshot of article on 88 Bar. Featured illustration by Wang XX.

During the early months of COVID-19, back when the outbreak was centered in China, I put down my artist’s pencils and, as a writer, sought out how fellow cartoonists in China were faring under the crisis. I scoured the China internet for their expressive works about the lockdown, the ennui, and the senseless deaths happening around them, and amplified their voices and works through channels available to me at the time. I compiled three articles worth of China under COVID-19 comics on 88 Bar, with translated excerpts and wrote about their works, together with comics from adjacent places and communities that were coming under fire from the pandemic, on Hyperallergic. These days, I’m helping the team at Paradise Systems translate and publish these comics in full, which we will be collected into a mini-anthology later this year.

2. Make art that calls in your community

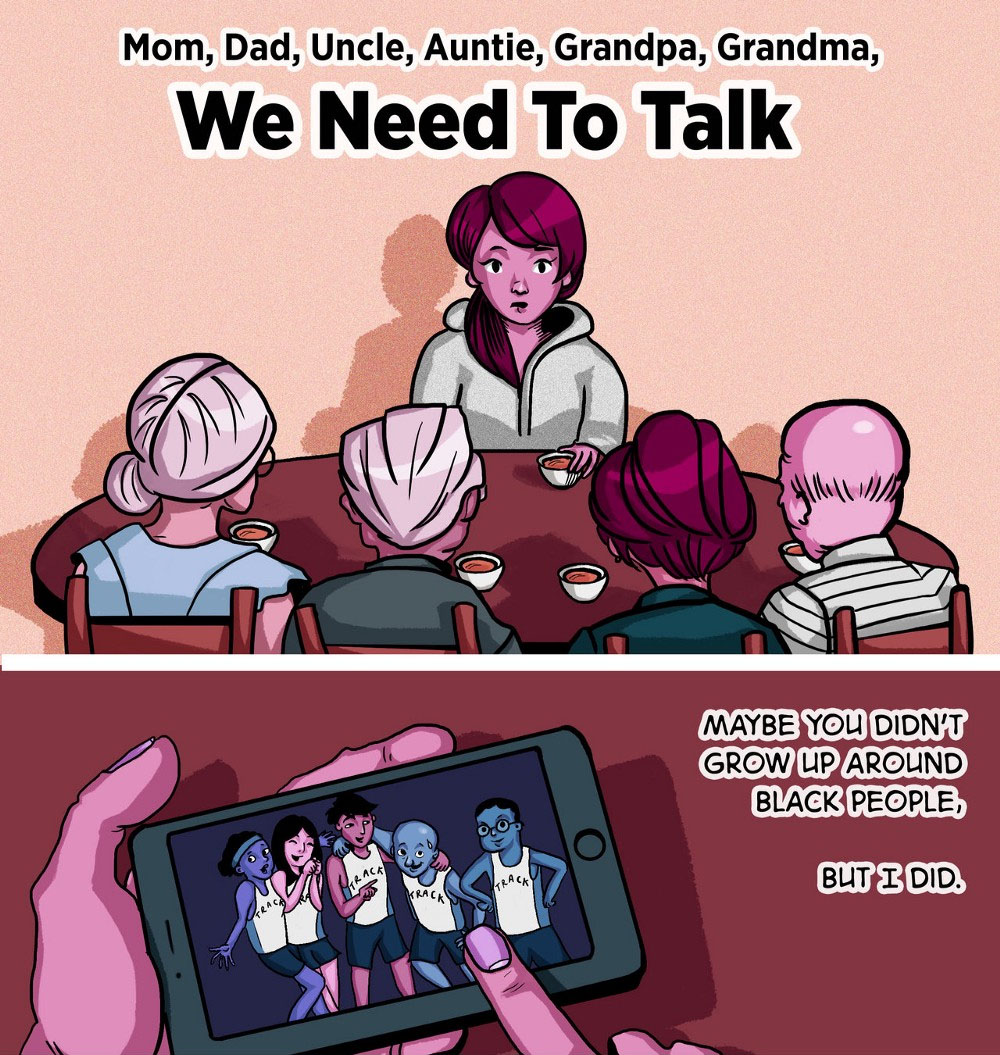

Letters for Black Lives comic adaptation by Wendy Xu, Jason Li, Jamie Parreno, Ellen Gezi, Michelle Xu, Carina Browder.

Initiated in 2016 and revised in 2020, the Letters for Black Lives project bridged the generational and language gap when it came to talking to our elders about police brutality and Black Lives Matter in North America. The project produced a heartfelt letter targeting first or second-generation immigrant parents to assuage their anxieties around the protests, and to explain the severe systemic injustices that Black folx face every day. Localized into dozens of different languages and communities, the letter is meant to be sent directly to family members. While many of us did post various versions of the letter online (I worked on a comics version), it is, as project member Gary Chou states, “not an open letter to all Black people from all the Asians telling them how much we love them and asking for a cookie in return.” He continues, “These are intra-community letters addressed to and written by non-Black people, mostly 1st, 1.5, 2nd gen immigrant families, not in the service of calling out your family, but as a way to start calling them in.”

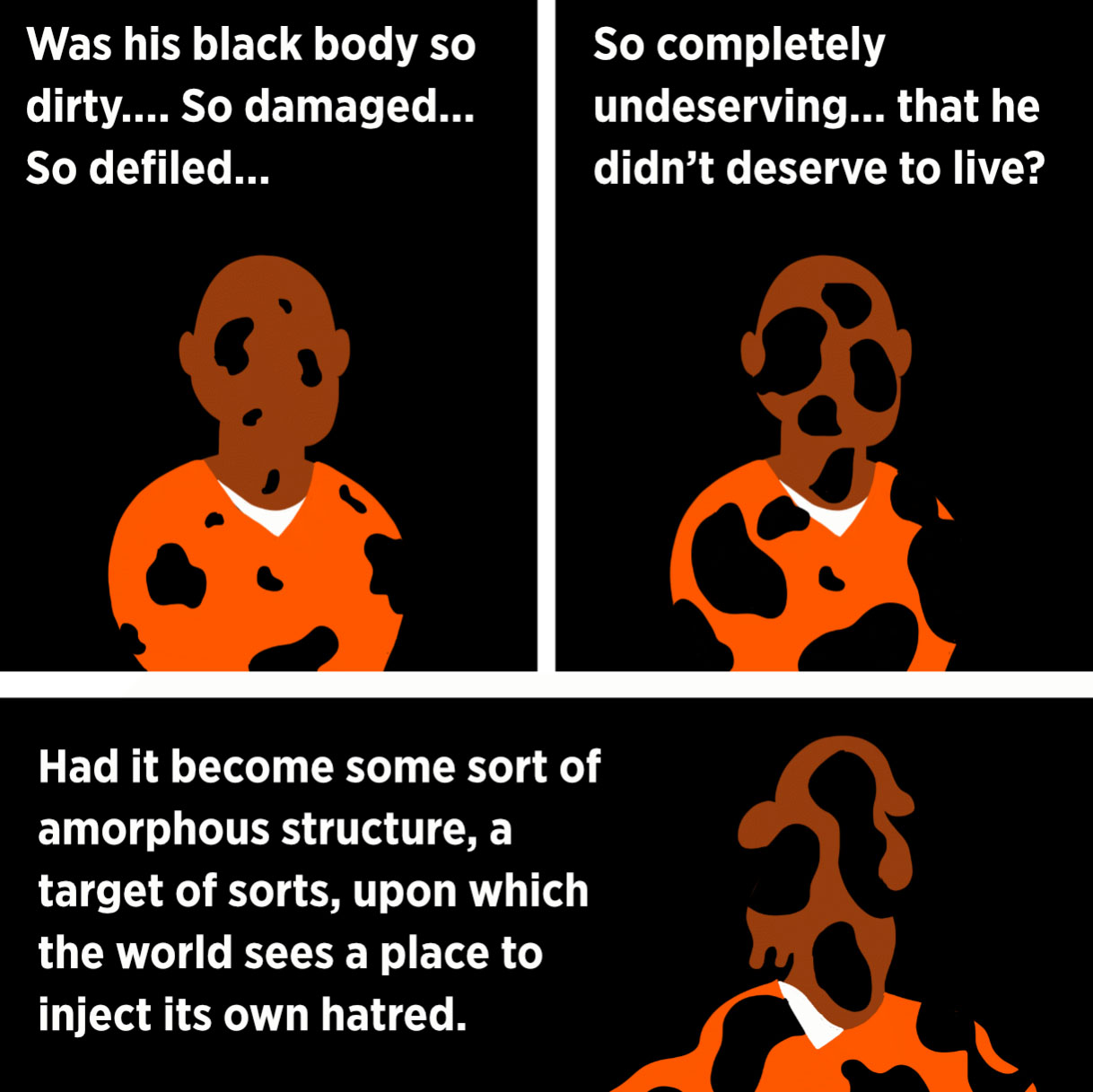

3. Make art that amplifies other people’s voices

Since 2014, my friends and I have been illustrating stories around various social movements as they are happening, including Black Lives Matter, as part of a webcomic series called Add Oil Comics. Our mandate is three-fold: highlight other people’s perspectives (particularly those on the ground) and amplify their actual written voices. We did this by taking existing writing on social media and turning an excerpt into a fully-illustrated comic strip. In the case of Black Lives Matter, we didn’t put ourselves in front of or on equal footing with Black folx; we stood in the background as support and as cheerleaders, even as a few of our strips went viral. We did so by crediting the original author first, by working under a group moniker, and by directing our marketing towards the story or news event (rather than towards ourselves and our efforts). As the writer for one of our works related to childhood trauma puts it, “Turns out someone putting pictures to your words is a pretty powerful way of hearing them and standing with them in their pain, together.”

4. Stand down as an artist

As a professional artist, the urge to respond to a pressing crisis is undeniable. When the Black Lives Matter movement resurfaced in 2020, I too felt the pull to illustrate the moment, to capitalize on my years of comics about the movement from 2014-2017. But it also felt wrong to do so. We were all already being inundated with news and images as well as stunning works of art on social media from the movement. What did I have to say that merited taking away airspace from Black protesters, organizers and artists during this critical moment? This time, I stood down as an artist. But as a person, I tried to support the movement in other ways, by showing up for friends, protests, fundraisers and helping out in whatever other capacities I could.

The phrase, “Don’t be an ally, be an accomplice” has been gathering steam in recent years. Embedded in it is the idea that if you truly wish to stand in solidarity with someone, you should be placing yourself at risk and be prepared to lose out. Allies have been maligned for operating at a safe remove — by clipping a safety pin to their lapel after the 2016 US elections or posting a black square on social media during the Black Lives Matter resurgence and “asking for a cookie” for their efforts afterwards. Accomplices do more — they use their physical bodies to protect Black folx at a protest, help run fundraisers for other groups, assist in clerical work behind the scenes, and challenge their own community leaders — without expecting a reward.

What then does it mean to be an artist-accomplice? I’ve outlined several beginning steps above, all of which start with one simple idea: cede the spotlight and de-center ourselves. If the primary outcome of our action ends up bringing attention to ourselves and our work, then we’ve failed as accomplices. Don’t be too quick to judge though, we’ve all been there, despite our best intentions. The artist from the beginning of this essay certainly had good intentions, and showed an admirable willingness to change after receiving both public and private feedback. It was a shame that the uproar online ended abruptly with a quick fix and hurried apology, robbing our larger community of the benefits of a deeper dialogue and more critical reflection.

I end this essay with an ask to all of us in the arts. Let’s talk about what it means to be an ally and an accomplice. Let’s figure out new avenues of expression, new collaborative practices, new ways of being that don’t pit us against the people we are trying to help. We are all learning together, and learning is often a painful, non-linear process. We will inevitably regress — an Asian arts organization recently ran a raffle fundraiser using a carpet version of the yellow tiger/black panther illustration — so let’s be prepared to be there for each other when we do and hold each other accountable. Let us be firm but gentle, open but persistent in our pursuit of a better world.