The short answer

Install the BabelStone Han font, which supports “57,000 Han characters… [and] includes many rare or archaic characters that are not found in most CJK fonts” on your computer. Then look up the character on Unicode’s Unihan Database Lookup website (using the Stroke-Radical Index) and copy-and-paste it from there.

Update: Andrew West, the maintainer of BabelStone Han font, wrote in and pointed out that it is quicker to find the character by opening BabelStone Han’s IDS (Ideographic Description Sequences) text file in a web browser or text editor, and running a search using the type-able parts of the character.

How we got here: the back story

I met scholar and translator Clement Tong at the Translating Hong Kong 2 symposium recently, and he had a pressing request for the designers in the room. He wanted us to find a way to make it possible to typeset (i.e. type and print) a set of very rare, but historically significant, Chinese characters. These esoteric characters appear in his research on the earliest Chinese-language Bibles, which, as his article in Christianity Today points out, date back to the early 18th and 19th centuries.

As a designer, I knew that the answer to his request actually consists of two parts:

- Is there a Unicode code point for these characters? I.e. is there a piece of computer code that allows the seldomly-used Chinese characters to be typed (or, more likely than not, copied-and-pasted like a symbol)?

- If so, is there a font that will display these characters? I.e. is there a Chinese font with a wide-enough character set that will display the seldomly-used character?

I asked Clement for a sample of some characters that he had been, until now, unable to typeset, and he sent me the following examples (also from the Christianity Today article):

- [口撒]

- [口所]

- [口瓦]

They are written with square brackets to indicate that the two characters are supposed to be combined into one. For example, using this notation, the character for the sound of laughter, 哈, would be written as [口合].

How we got here: the answer explained

The first thing I did was download the BabelStone Han font, “a free Unicode CJK font with over 57,000 Han characters (hanzi, kanji, hanja), and 62,061 Unicode characters in total… includes many rare or archaic characters that are not found in most CJK fonts, as well as many characters used for the scholarly transcription of Early Chinese texts written on bone, bronze, wood, bamboo, and silk.” The font is free courtesy of BabelStone, who are building on top of previous work done by Taiwanese type foundry Arphic.

Then I installed the font on my computer. (Here are the instructions for macOS and Windows 10/11.) I didn’t bother trying to install them on my mobile devices, since that process requires complicated third-party apps. With the font installed, my computer was now able to display many more Chinese characters.

To test the new font, and to look for our characters, I went to Unicode’s Unihan Database Lookup website. I clicked on the site’s Radical-Stroke Index. I started by looking up the first of Clement’s requested characters: [口撒]. It’s written with a 口 radical, which takes three strokes to write, and I navigated to the corresponding Radical-Stroke Index for radical #30 (mouth) 口. Then I counted the number of strokes in the rest of the character, 撒, which is 15. I scrolled down to look for it.

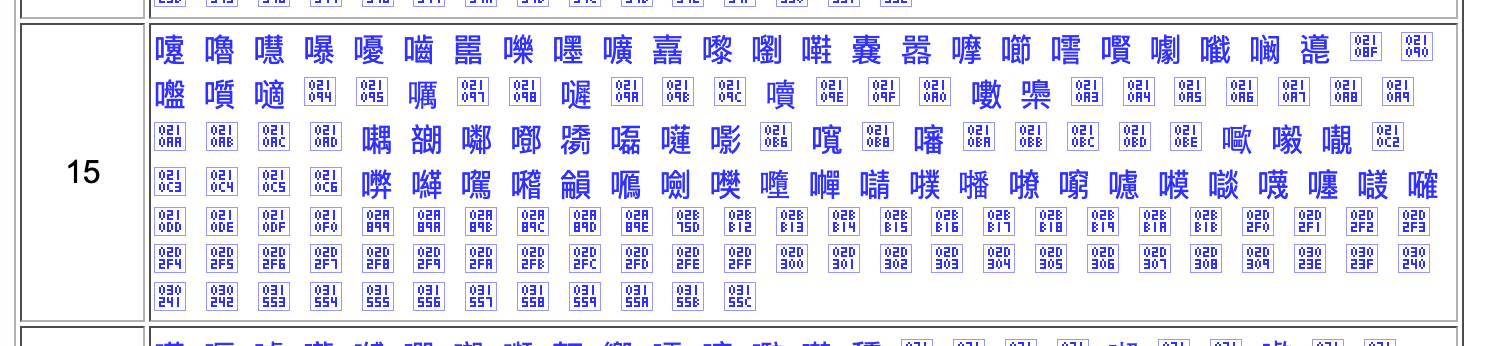

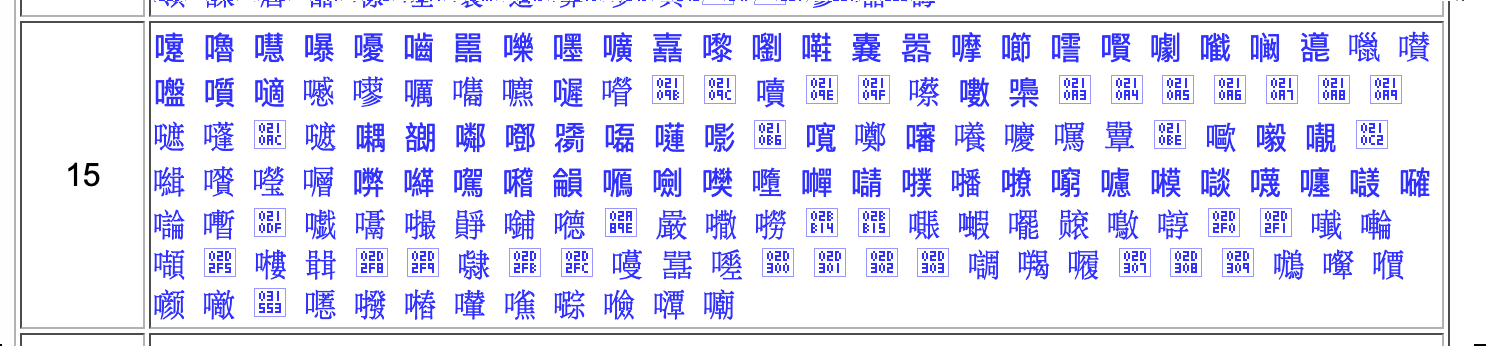

Before installing the font, this is what the search results look like – the square blocks with random letters inside indicate that my computer can’t find a corresponding font to display that character:

Aftering installing the font, most of the square blocks become legible Chinese characters:

I eventually located [口撒] in the middle of the fifth row. I clicked on it to land on the page on Unicode for [口撒]. There I could easily select the character to copy-and-paste into whatever documents I needed. I quickly fired up Adobe Illustrator to paste the characters in and enlarged them to show Clement.

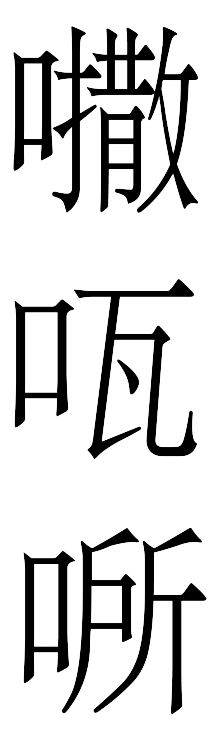

I went through the same sequence of lookup, copy and paste for the remaining two characters. Here are the three characters Clement asked me about, rendered with the BabelStone Han font:

Update: As we mentioned at the beginning of the article, one quicker alternative to looking up the character on Unicode’s website is to look within BabelStone Han’s IDS (Ideographic Description Sequences) text file. In the case of the first example, all you have to do is open the file in a web browser or text editor and search directly for “口撒” to locate the character.

How we got here: caveats

Two things to keep in mind about this process:

- If you copy and paste these esoteric characters onto a website or Word/Google Doc document, the characters will only show up if the person viewing it has the BabelStone Han font installed. Luckily, they will show up if you export a document into a PDF or print a physical copy.

- For many of these esoteric characters, the only font that supports them is the Babelstone Han font, which means that they will follow its visual design as a “Song/Ming style (宋体/明體) font, with glyphs modeled on the official character forms used in the People’s Republic of China.” More font options may open up in the future, but no other font I found today works on these rare historical characters, including the expansive Source Han and Noto projects by Adobe, Google and partners

This article was first cross-posted to both 88 Bar.